KAWADE SHOBO SHINSHA Ltd. Publishers Bookmark

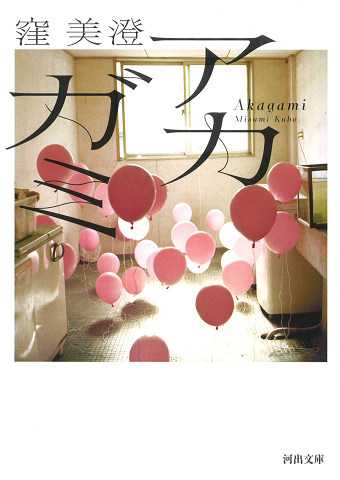

Aka gami

Information will be available after you log in. Please create an account.

Rights Information

Other Special Conditions

Abstract

An accomplished foray into speculative fiction by an author lauded for her unflinching realism, Redpaper is a powerfully fresh love story evolving from within a dystopian near-future setting, making for a read that is both thought-provoking and compulsive.

The protagonist, a young woman called Mitsuki, is first introduced to us first by the researcher and sex worker Log. From within her near-future viewpoint, Log presents Mitsuki as a prime example of the new generation of youngsters who have no desire for romance, sex, friendship or intimacy with others, and among whom the suicide rate is phenomenally high. Mitsuki works in a care home for the elderly, and her life consists in coming and going between there and the apartment in which she lives with her mother, who has been bedridden with severe depression since Mitsuki’s father left her for a younger woman. We learn that Log and Mitsuki first struck up a friendship after Log found Mitsuki collapsed in the toilets of a bar after taking an overdose. Since then, the two have been meeting in that bar after Log’s day of sex work finishes, and gradually becoming friends. It is through Log that Mitsuki learns of the existence of Redpaper, a new government scheme where people of childbearing age are handsomely rewarded to live with a member of the other sex that they’re matched with and have children. Not only this, but their family members are also given full care and catering.

Her curiosity piqued, Mitsuki decides to apply to Redpaper, and attends the weeklong training course. Some participants drop out when they discover the details of the scheme—specifically, the cohabitation, sex and childbirth entailed—while others are rejected on the basis of the rigorous health screenings. Mitsuki passes, however, and promptly begins her new life in the apartment complex surrounded by a great wall manned by security guards. After a few hours in her new apartment, her “mate” enters: Satsuki is a polite, good-natured young archaeologist employed in a museum.

Initially, daily life with someone else is terrifying. Mitsuki finds it excruciatingly difficult to articulate her feelings and thoughts on anything, and worries obsessively that Satsuki will request a transfer to another partner, or desire her physically.

Gradually, though, the two grow closer. To her surprise, Mitsuki begins to understand how grounding an emotional connection with someone can be: she finds that knowing Satsuki is at home is “like a heavy stone inside her”, a feeling that she likes. Satsuki confides in her that he enrolled in the programme to ensure that his family had enough to eat; he didn’t have any interest in finding a partner. Yet he reassures Mitsuki that although that was his motivation, he genuinely is glad that he had ended up with her. Eventually they have sex, and before all that long, Mitsuki is pregnant. The pair is aware that into the late stages of pregnancy, couples leave the complex and are taken somewhere else, but they are given no details about where. Speculating on this, they realise that actually, they haven’t thought much about what awaits them in the future of the programme.

Indeed, as the pair’s love grows, so does their awareness of the sinister elements of their lives. Increasingly, Satsuki feels stifled by their situation, remarking to Mitsuki that the complex feels a bit like a zoo, where they are the endangered animals, lavished with excessive care and attention, forbidden to roam free. From the window of the apartment belonging to a woman Mitsuki strikes up a friendship with, she sees protesters with loudspeakers who are then dispersed by the security guards.

The pair’s sense of claustrophobia only intensifies when they move into their new apartment complex, even more heavily guarded, where assistants come in to do their cleaning and their cooking for them. Just as Satsuki is about to tell Mitsuki of some bad rumours he’s heard about the Redpaper programme, Mitsuki’s waters break, and she is rushed to hospital. The account shifts into Satsuki’s perspective here, and we learn that he found a piece of paper on the street outside the complex, saying that the babies born to Redpaper in fact become “government property”. Googling the word “redpaper” he learns that “red paper” was the unofficial name for a conscription letter in the Second World War. He calls Log to confirm this, and she apologises, saying that at the time she encouraged Mitsuki to apply she hadn’t been aware of that aspect of the programme, before hanging up.

The sinister aspects to the Redpaper scheme are confirmed beyond doubt when Mitsuki’s baby is born with a sixth finger, and as a result is deemed “unsuitable”. With this decision, the couple’s treatment undergoes a 180° shift. They are informed robotically by two black-suited men that they have three days in which to clear their stuff and leave. The security personnel who were formerly so polite and protective now ignore them. Back in their apartment, everything—food, furniture, baby equipment—is gone. Their family members stop receiving any subsidies or care.

The novel ends as the new family get in their car and drive away forever from the Redpaper complex, with no place to go, no idea how to survive in the world as parents, desperately needing formula milk and not knowing where to buy it. Yet Satsuki nonetheless finds himself struggling to hold back a smile. At least, he thinks, they are free.

One of the most inviting aspects of Redpaper is how, in taking as its protagonists those to whom intimacy is an alien concept, it is able to narrate processes like falling in love, having sex for the first time and pregnancy in a way that feels genuinely fresh and touching. Yet if the reader takes simple joy in these heteronormative life-goals, there is also simultaneously a tremendous subversion of them: the world has progressed so that these things once heralded as “natural” can now only occur in the most highly orchestrated of circumstances. More than that, this joy is essentially being coopted for the “good” of the nation. In fluid, clear-sighted prose, Kubo complicates our concepts of familial love, intimacy, and productivity.

Like the best science fiction, Redpaper not only outlines a vision of the future, but sheds light on the present we are living, in both the sensations it engenders and the socioeconomic forces at work. The opening section told from the perspective of sex worker Log are fascinating in pointing towards the future that lies ahead if the very real issues of decreasing birth rate and diminishing desire for marriage and intimate relationships among young people continue unabated. The sections told from the perspective of Mitsuki and Satsuki, meanwhile, narrate a skillful internal description of what it is like to occupy that mentality, and grow up without any need for closeness to others.

It should be noted also that Redpaper has a highly cinematic quality, bold, striking and riddled with potent symbolism, in a manner reminiscent of Naomi Alderman, Margaret Atwood and Elif Shafak. The underlying concept for the book feels powerfully simple, yet the details and descriptions are impressively real. The sense of foreboding that builds throughout is rendered with skill, yet the idea that the babies born will become cannon fodder, as is suggested, still manages to come as a surprise, and provides a new lens through which to evaluate what has come before. Western readers will find much to relate to in this uniquely Japanese take on dystopian fiction. Is the world where the human capacities for intimacy and reproduction are coopted by the state so far away from our own?

Author’s Information

Since her debut in 2009 which won the R-18 Literary Award, Misumi Kubo has been one of Japan’s most-loved novelists, her novels dealing in her characteristically frank style with issues such as parenthood, marriage, sex, intimacy, and ageing. In 2020, she won the highly prestigious Naoki Prize for her novel Releasing Stars Into the Night. The first full-length English translation of her work, So We Look to the Sky was published by Arcade in 2021. Her work has been adapted for film and television, including the 2012 film The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky.

| Series/Label | --- |

|---|---|

| Released Date | Oct 2018 |

| Price | ¥580 |

| Size | --- |

| Total Page Number | 280 pages |

| Color Page Number | --- |

| ISBN | 9784309416380 |

| Genre | Literature / Novel > Japanese Literature |

| Visualization experience | NO |