Kobunsha Bookmark

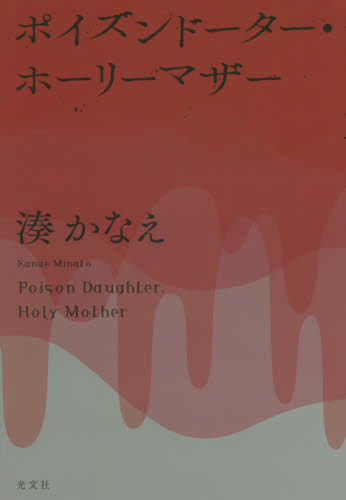

Poison Daughter, Holy Mother

Information will be available after you log in. Please create an account.

Rights Information

Other Special Conditions

Abstract

A novel in eight short stories involving incidents of murder, injurious assault, and such by a writer regarded as the originator and queen of the genre known as iyamisu in Japan—literally, “eww mysteries.” The term refers to mystery fiction in which the darker impulses rooted deep in human nature—jealousy, vainglory, narcissism, malice, cruelty, etc.—figure to eww-inducing effect. The last two stories in the volume, titled “Poison Daughter” and “Holy Mother,” center on the same incident from the respective viewpoints of two women who were classmates in secondary school, and they can be read together as a single novella. As shown here once again, author Kanae Minato especially shines when giving voice to “bad women” recounting their stories in the first person.

“Poison Daughter” is told from the perspective of Yumika, a 33-year-old actress, while “Holy Mother” is told from that of Riho, a stay-at-home mother Yumika has known since her school days. The main theme is that of toxic parenting, in which the mother maintains such absolute and oppressive control over her child that the child cannot develop his or her own identity.

Yumika relates how she was treated by her mother. When she was three, her father died in an automobile accident. After that, her mother Yoshika took a job as a clerical worker at a high school to support herself and her daughter. Yumika wanted to become a writer, but Yoshika was determined that she would follow in her father’s footsteps as a language-arts teacher, and steered her in that direction from a young age. She banned both manga and boys for her daughter, and screened all her friends. She allowed Yumika to go away from home to Tokyo for college, but only on condition that it be a women’s school with dormitories, that she major in education, and that she return home to teach locally once she graduated. Although Yumika suffered constant headaches from the stress, she nevertheless continued to do as her mother wished. She failed the employment test for a teaching position, however, and was working as a temp in the tourism office at city hall when she was scouted to be an actress and returned to Tokyo eight years ago.

To Yumika’s eyes, her best friend Riho suffered from a toxic mother as well, though of a different style.

Riho’s father ran a real estate agency, and her mother was an affluent homemaker. The first time Yumika visited Riho’s house, she was surprised at how young her mother looked—almost as if she and Riho were sisters—and she envied Riho for having a mother who was such an excellent cook, unlike her own mother. But as they grew up Yumika came to realize that Riho was being completely controlled by her mother, who had spoiled Riho to the point that she couldn’t live without her. Even though Riho made top grades and could have gone to a competitive school, her mother insisted junior college was good enough for her, saying she would arrange a marriage for her to a man who could manage the family business. She seemed to be trying to turn Riho into a copy of herself. Riho did go out with the prospective husband her mother found for her, but ultimately chose to elope with the man she loved instead.

When Riho suggests that they go to their high school reunion together, Yumika turns her down because going home would mean she’d have to see her mother. A month or so later Yumika begins making remarks about toxic mothers during TV appearances. Without naming names, she tells both Riho’s story and her own, and several months later she goes on to publish a book titled Daughters under Their Mothers’ Thumb. When she first started speaking up, Yumika worried that an infuriated Yoshika might come to Tokyo and stab her to death, but instead, not long after her book appears, her mother dies in a traffic accident. Some media outlets speculate that Yoshika became depressed after Yumika’s revelations and deliberately threw herself in front of the truck that killed her.

In “Holy Mother,” Riho turns everything the reader has come to understand from Yumika’s narrative upside down. Riho never regarded Yumika as a best friend. She polishes up a denunciatory statement written by her stepmother, who was a friend of Yoshika and had looked after Yumika as a daycare provider, and sells it to a weekly magazine. She spreads the view that, back home, Yoshika was regarded as a saint and the perfect mother, adding fuel to the speculation that it was the evil Yumika who drove her to suicide. Unaware that Riho has stabbed her in the back, Yumika turns to her for help in tracking down the person who is spreading malicious stories.

The titles in the collection vividly highlight the gap between the public face and the true colors of the characters involved, the tenuousness of the “truths” being tossed about in the media and on the Internet, and how members of contemporary society are constantly being jerked around by both. It is no doubt the way Minato cracks open her characters’ public personas to reveal their true natures that is winning her so many fans.

Author’s Information

Kanae Minato (1973–) was, even as a child, a passionate fan of Maurice Leblanc and Edogawa Rampo. After graduating from university she spent two years in Tonga as a Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer, returning home to become a high-school home economics teacher and later get married. She started writing in her thirties, initially hoping to become a scriptwriter. In 2005 one of her scripts won an Excellence Award in a competition for new writers sponsored by a satellite TV channel, and another won the Radio Drama Composition Prize in 2007. That same year, Seishokusha (The Saint) won the Shōsetsu Suiri New Writers Prize, marking Minato’s debut as a writer of fiction. Kokuhaku (Confessions; tr. 2014), her first work published in book form and the first chapter of which is based on Seishokusha, received the 2009 Booksellers Award and became an overnight bestseller. Her 2011 title Hana no kusari (Chain of Flowers), a longitudinal history centered on three women, expanded the mystery genre in entirely new directions. In 2016 she received the Yamamoto Shūgorō Prize for Yūtopia (Utopia), a small-town ensemble story with a mystery twist. She was also nominated for both the Yoshikawa Eiji Prize for New Writers and the Naoki Prize, for Ribāsu (Reverse) and Poizun dōtā, hōrī mazā (Poison Daughter, Holy Mother) respectively, establishing her as an awards-list regular. Other works include Shōjo (Girl), Shokuzai (Atonement), and Yakō kanransha (Ferris Wheel at Night).

| Series/Label | --- |

|---|---|

| Released Date | May 2016 |

| Price | ¥1,400 |

| Size | --- |

| Total Page Number | 245 pages |

| Color Page Number | --- |

| ISBN | 9784334910945 |

| Genre | Literature / Novel > Mystery |

| Visualization experience | YES (A TV drama series in Japan.) |